Presented by INSA’s Insider Threat Subcommittee

Introduction

This paper assesses messaging from the Intelligence Community (IC) and the Department of Defense (DoD) regarding the examination of clearance applicants’ publicly available social media accounts. Social media in this paper refers to all forms of online networking platforms, to include: Discord, Facebook, Instagram, Telegram, and TikTok¹.

As the federal government adapts to rapidly changing technology and online behaviors by individuals using social media, it is imperative that it update policies and procedures associated with personnel vetting. Additionally, there is a need to improve messaging to the general public and the cleared community regarding how online conduct can impact eligibility for obtaining a clearance.

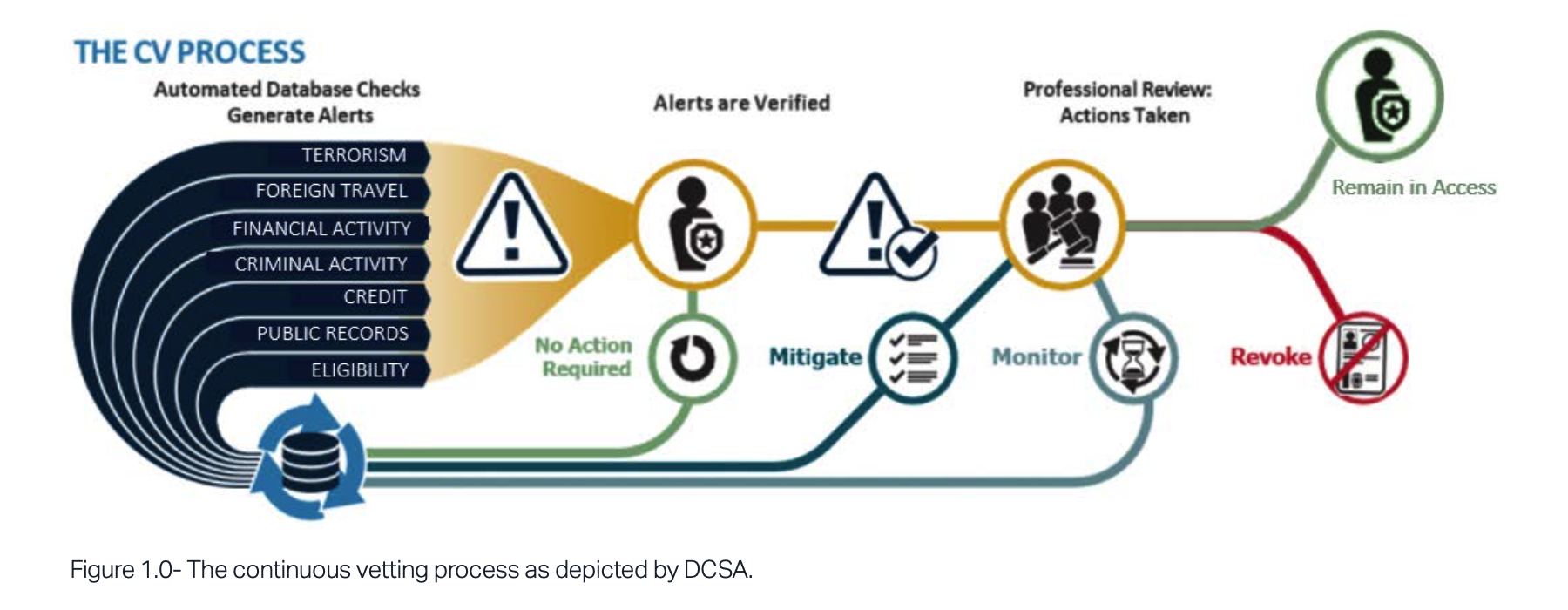

The Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency (DCSA) is currently implementing Trusted Workforce (TW) 2.0, a new paradigm for investigating candidates’ backgrounds and adjudicating clearances. An integral part of the TW 2.0 initiative is Continuous Vetting (CV), a regular automated review of seven categories of databases that provide insight into potentially concerning activities of cleared individuals. (See Figure 1.0.)

Social media is not one of the data sources consulted under Continuous Vetting. Government policy already permits agencies to collect social media data, but agencies have refrained from doing so because of a lack of guidance regarding how to navigate privacy concerns. While Security Executive Agent Directive 5 (SEAD-5) provided the authority to collect² social media for background investigations, it did not provide guidance on how to assess the information gathered during the adjudication process or how to collect it in a manner consistent with privacy-related statutes and policies.³

Between SEAD-5 authorities and DoD aspirations, the future of security clearance adjudications will likely include some review of publicly available social media information. The future and current cleared workforce need clear guidance from the federal government on how TW 2.0 and CV will address online behavior and how such behavior will influence decisions regardingclearance eligibility.

Impact of Social Media

Social media activities can produce digital indicators of personality attributes. Social media posts may disclose our innermost – or even just fleeting – thoughts. Geolocation metadata, facial recognition, and “likes” can divulge both online and real-world viewpoints and experiences. Some adults – not to mention young professionals at the outset of their careers – may not think about the implications of photos or comments that can present an overly transparent, or even misleading, image of ourselves. Americans often first access social media at a young age when they do not necessarily understand the ramifications of actions and statements that can remain publicly available forever. Moreover, as Americans become increasingly accustomed to meeting new persons online as part of their daily lives, they make themselves susceptible to being recruited by a malicious online contact– whether a con artist seeking a profit or a foreign intelligence officer with nefarious intent. Social media misinformation and disinformation has had a significant impact on the U.S. population and domestic political discourse. Events of January 6, 2021, highlighted how information can be manipulated to mobilize large groups of people to take violent political actions. In a study on the malignant influence that misinformation plays in American politics and society, the RAND Corporation coined the term “truth decay” to describe the “diminishing role that facts, data, and analysis play in our political and social discourse.4” RAND’s proposal to enhance social media literacy from early ages and at all levels of society is critical to ensure that the U.S. education system produces critical thinkers who can thrive as objective, informed analysts of global affairs. Truth decay and social media literacy have direct effects on individuals’ eligibility for security clearances.5 Dis/ Misinformation campaigns can lead an individual to follow, like, and engage with organizations whose intolerance renders a person ineligible for a clearance or makes him/ her a target for foreign intelligence entities. Government, private industry, and educational institutions should encourage the development of social media literacy training and awareness through organizations such as the Center for Development of Security Excellence (CDSE) to reduce the risk to future clearance holders and the IC’s recruitment pool as a whole.DoD Treatment of Social Media

The DoD has clarified its guidance to the workforce on social media activity related to violent domestic extremism. The updated DoDI 1325.06, “Handling Protest, Extremist, and Criminal Gang Activities Among Members of the Armed Forces,” November 27, 2009, as amended, states that online behavior can be considered for purposes of defining active participation in extremist activity:Engaging in electronic and cyber activities regarding extremist activities, or groups that support extremist activities – including posting, liking, sharing, re-tweeting, or otherwise distributing content – when such action is taken with the intent to promote or otherwise endorse extremist activities. Military personnel are responsible for the content they publish on all personal and public Internet domains, including social media sites, blogs, websites, and applications.6DoD has not yet applied this restriction to the personnel vetting process applied to job candidates or employees who seek a security clearance. If the DoD gathers social media information during the background investigation, they must explain how they will evaluate likes and retweets during the adjudication process. Cleared personnel are required to report actions by others that raise potential security or counterintelligence concerns. It is not apparent, however, whether questionable online activity constitutes such a concern and must therefore be reported. For example, SEAD-3 (“Reporting Requirements for Personnel with Access to Classified Information or Who Hold a Sensitive Position”) calls on cleared personnel to report “any activity that raises doubts as to whether another covered individual’s continued national security eligibility is clearly consistent with the interests of national security.”7 While DoDI 1325.06, characterizes the activities of potential concern when undertaken by military personnel, no policy document clearly defines what online activities by civilian personnel are potentially reportable. If a candidate likes a Facebook post by a white supremacist militia member, is that sufficient to raise questions about the suitability of the candidate? Does the number of likes matter, does the content of the liked post matter, or is it sufficient to simply be associated with a particular person or organization? Additionally, how much will the adjudication authority weigh social media activity against other forms of behavior?

Recommendations

Given the prevalence of social media use, and the need to consider it during the clearance vetting process, the following steps are recommended:

- The Director of National Intelligence (DNI), as the government’s Security Executive Agent (SecEA), should develop clear criteria for assessing personnel security risks of social media activity. Specifically, it should clarify how much the adjudication authority should weigh social media activity against other forms of behavior.

- SecEA should update SEAD-5 or its implementation guidelines so both employers and job candidates know how online conduct will be assessed during the adjudication process.

- The policy should define the types of online

activities by civilian personnel that are reportable, so employees know what behaviors to avoid and what to report if witnessed. - The updated SEAD-5 guidelines should clearly define what constitutes reportable social media activity. Additionally, how much will the adjudication authority weigh social media activity against other forms of behavior.

Conclusions

The DNI, as the government’s Security Executive Agent should develop clear criteria for assessing personnel security risks of social media activity. Such criteria may enhance the provision of guidance that more clearly and consistently communicates how social media behavior can affect clearance eligibility to cleared industry, job candidates, recruiters, investigators, and adjudicators. Everyone involved in the clearance process, including the applicant, must understand what online activity is prohibited or advised against if security and counterintelligence risks are to be mitigated. The government and private employers alike also need to make clear to their employees that the risks posed in social media use extend beyond the initial clearance process, and improper activity could affect their continued employment just as much as it affects the initial decision.

Additionally, clearer guidance on social media activity will help cleared industry improve prescreening and recruiting processes and maintain effective insider threat programs.

INSA expresses its appreciation to the INSA members and staff who contributed their time, expertise, and resources to this paper.

INSA Members

Sue Steinke, Peraton

Insider Threat Subcommittee Chair

Julie Coonce, Premise

Insider Threat Subcommittee Vice Chair

Eric Roscoe, SANCORP Consulting, LLC

Margaret Cunningham, PhD, Cunningham Consulting Leslie Cooper, Ball Aerospace and Technologies Corp.

INSA Staff

Suzanne Wilson Heckenberg, President

John Doyon, Executive Vice President

Bishop Garrison, Vice President for Policy

Peggy O’Connor, Director of Communications and Policy Larry Hanauer

Hailey Epler, Intern

Sam Somers, SkillBridge Fellow

About INSA’s Insider Threat Subcommittee

INSA’s Insider Threat Subcommittee researches, discusses, analyzes, and assesses counterintelligence and insider threat issues that affect government agencies, cleared contractors, and other public and private sector organizations. The Subcommittee works to enhance the effectiveness, efficiency, and security of government agencies and their industry partners, as well as to foster more effective and secure partnerships between the public, private and academic sectors.